2. The Main Players In The Forex Market

When the US Dollar went off the gold standard and began to float against other currencies, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange began to create currency futures to provide a place where banks and corporations could hedge the indirect risks associated with dealing in foreign currencies.

More recently, currency gyrations have centered on a massive move away from currency futures to more direct trading in the Forex spot markets where professional currency traders, alongside with forwarding contracts, derivatives of all kinds, deploy their various trading and hedging strategies.

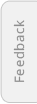

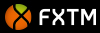

The idea of currency speculation has been actively marketed, and this is having a profound effect on the foreign exchange planning not only of nations - through their central banks - but also of commercial and investment banks, companies and individuals. These are the main categories of participants - a geographically disperse Forex clientele - and as a consequence so is the market as a whole. In practice, the foreign exchange market is made up of a network of players clustered in various hubs around the globe.

The key difference among these market participants is their level of capitalization and sophistication, where the elements of sophistication mainly include: money management techniques, technological level, research abilities and level of discipline.

Among the market players it is the individual trader who has the least amount of capitalization. In the absence of this strength, besides of emulating those other elements of sophistication of the institutional players, individual traders are forced to impose discipline on their trading strategies.

Those who can impose discipline will gain the ability to extract positive returns from the Forex markets.

The players we're reviewing in this section are:

- Commercial And Investment Banks

- Central Banks

- Businesses & Corporations

- Fund Managers, Hedge Funds and Sovereign Wealth Funds

- Internet Based Trading Platforms

- Online Retail Broker-Dealers

Commercial And Investment Banks

Let's start dissecting the bigger players: the banks. Though their scale is huge compared to the average retail Forex trader, their concerns are not dissimilar to those of the retail speculators. Whether a price maker or price taker, both seek to make a profit out of being involved in the Forex market.

What is a market maker? To be considered a foreign exchange market marker, a bank or broker must be prepared to quote a two-way price: a bid price which is the market makers' buying price and an offer price is their selling price to all inquiring market participants, whether or not they are themselves market makers.

Market markers capitalize on the difference between their buying price and their selling price, which is called the "spread". They are also compensated by their ability to manage their global FX risk using not only the mentioned spread revenues but also netting revenues and revenues on swaps and conversions of residual profits or losses.

The exchange rates can be declared through foreign exchange dealers across the globe over the telephone or electronically via digital dealing platforms.

There are hundreds of banks participating in the Forex network. Whether big or small scale, banks participate in the currency markets not only to offset their own foreign exchange risks and that of their clients, but also to increase wealth of their stock holders. Each bank, although differently organized, has a dealing desk responsible for order execution, market making and risk management. The role of the foreign exchange dealing desk can also be to make profits trading currency directly through hedging, arbitrage or a different array of strategies.

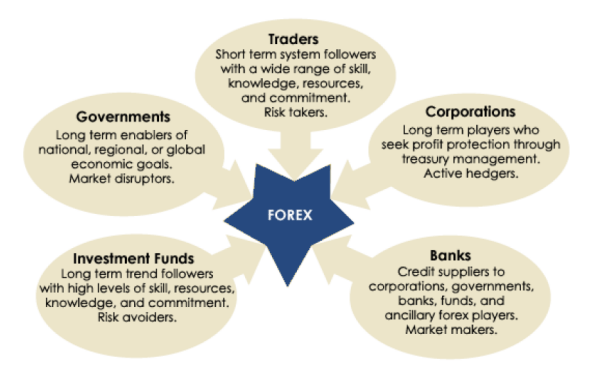

Accounting for the majority of the transacted volume, there are around 25 major banks such as Deutsche bank, UBS, and others such as Royal bank of Scotland, HSBC, Barclays, Merrill Lynch, JP Morgan Chase, and still others such as ABN Amro, Morgan Stanley, and so on, which are actively trading in the Forex market.

Among these major banks, huge amounts of funds are being traded in an instant. While it is standard to trade in 5 to10 million Dollar parcels, quite often 100 to 500 million Dollar parcels get quoted. Deals are transacted by telephone with brokers or via an electronic dealing terminal connection to their counter party.

Many times banks also position themselves in the currency markets guided by a particularly view of the market prices. What probably distinguishes them from the non-banking participants is their unique access to the buying and selling interests of their clients. This "insider" information can provide them with insight to the likely buying and selling pressures on the exchange rates at any given time. But while this is an advantage, it is only of relative value: no single bank is bigger than the market - not even the major global brand name banks can claim to be able to dominate the market. In fact, like all other players, banks are vulnerable to market moves and they are also subject to market volatility.

Similar to your margin account with a broker, the banks have established debtor-creditor agreements between themselves, which make the buying and selling of currencies possible. To offset the risks of holding currency positions taken as a result of customer transactions, the banks enter into reciprocal agreements to quote each other throughout the day on preset amounts.

Direct dealing agreements can include that a certain maximum spread will be upheld, except under extreme conditions, for example. It can further include that the rate would be supplied in a reasonable amount of time.

For instance, when a costumer wants to sell 100 million Euro, the procedure is as follows: the bank's sales desk receives the costumer's call and inquires the dealing desk at which exchange rate they are able to sell to the costumer. The costumer can now accept or deny the offered rate.

As a market maker, the bank has to handle the order in the interbank market and assume the risk for that position as long as there is no counterpart for that order.

Let's assume that the customer accepts the bank's buy price then the Dollars are immediately credited to the customer. The bank has now an open short position over 100 million Euro and has to find either another costumer order to match with this order, or a counter party in the interbank market. To do such transactions, most banks are nourished by electronic currency networks in order to offer the most reliable price for each transaction.

The interbank market can therefore be understood in terms of a network, consisting of banks and financial institutions which, connected through their dealing desks, negotiate exchange rates. These rates are not just indicative, they are the actual dealing prices. To understand the uniformity of prices, we have to imagine prices being instantaneously collected from crossed prices of hundreds of institutions across an aggregated network.

Besides of the available technology, the competition between banks also contributes to the tight spreads and fair pricing.

Central Banks

The majority of developed market economies have a central bank as their main monetary authority. The role of central banks tends to be diverse and can differ from country to country, but their duty as banks for their particular government is not trading to make profits but rather facilitating government monetary policies (the supply and the availability of money) and to help smoothen out the fluctuation of the value of their currency (through interest rates, for example).

Central banks hold foreign currency deposits called "reserves" also known as "official reserves" or "international reserves". This form of assets held by central banks is used in foreign-relation policies and indicates a whole lot about a countries' ability to repair foreign debts and also indicates a nation's credit rating.

While in the past reserves were mostly held in gold, today they are mainly held in Dollars. It is common for central banks nowadays to possess many currencies at once. No matter what currencies the banks own, the Dollar is still the most significant reserve currency. The different reserve currencies that central banks hold as assets can be the US Dollar, Euro, Japanese Yen, Swiss Franc, etc. They can use these reserves as means to stabilize their own currency. In a practical sense this means monitoring and checking the integrity of the quoted prices dealt in the market and eventually use these reserves to test market prices by actually dealing in the interbank market. They can do this when they think prices are out of alignment with broad fundamental economic values.

The intervention can take the form of direct buying to push prices higher or selling to push prices down. Another tactic that is adopted by monetary authorities is stepping into the market and signaling that an intervention is a possibility, by commenting in the media about its preferred level for the currency. This strategy is also known as jawboning and can be interpreted as a precursor to official action.

Most central bankers would much rather let market forces move the exchange rates, in this case by convincing market participants to reverse the trend in a certain currency.

Paolo Pasquariello explains price action in proximity to interventions stating:

Central Bank interventions are one of the most interesting and puzzling features of the global foreign exchange (forex) markets. More often than usually believed, domestic monetary authorities engage in individual or coordinated efforts to influence exchange rate dynamics. The need to strengthen or resist an existing trend in a key currency rate, to calm disorderly market conditions, to signal current or future stances of economic policy, or to replenish previously depleted foreign exchange reserve holdings are among the most frequently mentioned reasons for this kind of operations.

As you see, holding reserves is a security and strategic measure. By spending large reserves of foreign currency, central banks are able to keep the value of their currency high. If they instead sell their own currency they are able to influence its price towards lower levels. The consequence of central banks having purchased other currencies in an attempt to keep their own currency low results, however, in larger reserves. The amount central banks hold in reserves keeps on changing depending on monetary policies, on supply and demand forces, and other factors.

In extreme circumstances, for instance after a strong trend or imbalance in a currency exchange rate, keep a close eye on central bankers rhetoric and actions, as an intervention may be adopted in an attempt to reverse the exchange rate and nullify a trend set by speculators. This is not something which happens often but can be seen specially at times when exchange rates get a bit out of hand, either falling or rising too rapidly.

At those times central banks may step in in order to generate a specific reaction. They know the market participants pay close attention to them and respect their comments and actions. Their sheer financial power to borrow or print money gives them a huge say in the value of a currency. The opinions and comments of a central bank should never be ignored and it is always good practice to follow their comments, whether in the media or on their website.

You can follow all central bank related topics and news, through our RSS.

Interventions may work for a certain period of time. The Bank of Japan has the most active track record in that regard, while other countries have traditionally taken a hands-off approach when it comes to the value of their currencies.

In March 2009 the Swiss National Bank announced it would intervene in the currency market buying foreign currencies to prevent a further appreciation of the Swiss franc. As a result, the Swiss franc weakened significantly and EUR/CHF jumped more than 3% higher. Kasper Kirkegaard from Danske Bank A/S reports the tactic in one of his reports.

Businesses & Corporations

Not all participants have the power to set prices as market makers. Some just buy and sell according to the prevailing exchange rate. They make up a substantial allotment of the volume being traded in the market.

This is the case of companies and businesses of any size from a small importer/exporter to a multi-billion Dollar cash flow enterprise. They are compelled by the nature of their business - to receive or make payments for goods or services they may have rendered - to engage in commercial or capital transactions that require them to either purchase or sell foreign currency. These so called "comercial traders" use financial markets to offset risk and hedge their operations. Non-commercial traders, instead, are the ones considered speculators. It includes large institutional investors, hedge funds and other entities that are trading in the financial markets for capital gains.

In an article taken from the Forex Journal, a special edition by Trader's Journal magazine in November 2007, Kevin Davey details in funny words why you should mimic non-comercial traders:

One automobile company recently attributed a large portion of its earnings to its Forex trading activities. These groups should strike fear into the little minnows because these groups are the professional sharks. These organizations trade day and night, know the ins and outs of the market and eat the weak. Big moves in the market are usually the result of the activities of professionals, so following their lead and following the trends they start may be a good strategy.

In the same waters that the professional sharks swim, there are also a lot of minnows. They are also your competition, so knowing their tendencies can help you exploit them. For example, unsophisticated minnow'traders are likely to put stop-loss orders at obvious support or resistance levels. Knowing this, you can exploit this tendency and feed on them.

Also, think about the first sure thing chart formation that you ever learned about. Chances are that new traders are just learning about that formation now, so you could fade their trades and likely do all right. Think of it this way - defeating a foe sitting at his desk in his home office trading the Forex market in his bunny slippers is probably easier than defeating an MBA with a $5000 suit who trades via complex neural network arbitrage programs. So, try to mimic and follow the sharks and eat the minnows.'This is where having a plan to make you a more agile 'minnow' or even turn you into a 'shark' is critical.

Fund Managers, Hedge Funds and Sovereign Wealth Funds

With Forex trading surging in recent decades, and as more individuals earn their living trading, the popularity of riskier investment vehicles like hedge funds has increased. These participants are basically international and domestic money managers. They can deal hundreds of millions, as their pools of investment funds tend to be very large.

Because of their investment charters and obligations towards their investors, the bottom line of the most aggressive hedge funds is to achieve absolute returns besides of managing the total risk of the pooled capital. Foreign exchange advantage factors like liquidity, leverage and relatively low cost create a unique investment environment for these participants.

Generally speaking, fund managers invest on behalf of a range of clients including pension funds, individual investors, governments and even central banks. Also government-run investment pools known as sovereign wealth funds have grown rapidly in recent years.

This segment of the foreign exchange market has come to exert a greater influence on currency trends and values as time moves forward.

Another type of funds, made up of government-run investment pools, are "sovereign wealth funds". Read more about this subject.

Internet Based Trading Platforms

One of the great challenges to the institutional Forex and how exchange related businesses are being handled has been the emergence of the Internet-based dealing platforms. This medium contributed to form a diverse global market where prices and information are freely exchanged.

As evidenced by the emergence of electronic brokering platforms, the task of customer/order matching is being systematized as these platforms act as direct access points to pools of liquidity. The human element of the brokering process - all the people involved between the moment an order is put to the trading system until the moment it is dealt and matched by a counter party - is being reduced by the so called "straight-through-processing" (STP) technology.

Similar to the way we see prices on a Forex broker's platform, a lot of interbank dealing is now being brokered electronically using two primary platforms: the price information vendor Reuters introduced a web based dealing system for banks in 1992, followed by Icap's EBS - which is short for "electronic brokering system"- introduced in 1993; replacing the voice broker.

Both the EBS and Reuters Dealing systems offer trading in the major currency pairs, but certain currency pairs are more liquid and are traded more frequently over either EBS or Reuters Dealing. For instance, EUR/USD is usually traded through EBS while GBP/USD is traded through Reuters Dealing.

Cross currency pairs are generally not quoted on either platform, but are calculated based on the rates of the major currency pairs and then offset through the legs. Some exceptions are EUR/JPY and EUR/CHF which are traded through EBS and EUR/GBP which is traded through Reuters.

Kathy Lien explains the cross rating in one of her articles:

For example, if an interbank trader had a client who wanted to go long EUR/CAD, the trader would most likely buy EUR/USD over the EBS system and buy USD/CAD over the Reuters platform. The trader then would multiply these rates and provide the client with the respective EUR/CAD rate. The two-currency-pair transaction is the reason why the spread for currency crosses, such as the EUR/CAD, tends to be wider than the spread for the EUR/USD.

The minimum transaction size of each unit that can be dealt on either platforms tends to one million of the base currency. The average one-ticket transaction size tends to five million of the base currency. This is why individual investors can't access the interbank market - what would be an extremely large trading amount (remember this is unleveraged) is the bare minimum quote that banks are willing to give - and this is only for clients that trade usually between $10 million and $100 million and just need to clear up some loose change on their books.

As mentioned above, the interbank market is based on specific credit relationships between banks. In order to trade with other banks at the rates being offered, a bank may use bi-lateral , or multi-lateral order matching systems, which have no intermediary bank or dealer. These unofficial foreign exchange platforms, like the ones mentioned earlier, have emerged in the absence of a worldwide centralized exchange.

In the early 90s, when these interbank platforms were introduced, it is also when the FX market opened for the private trader, breaking down the high minimum amount required for an interbank transaction.

Along with banks, non-banking Forex participants of all types are being given a choice of available trading and processing systems for all scales of transactions. Around the same time as interbank platforms were introduced, web based dealing systems that corporations could use in lieu of calling banks on the phone also began to appear. These trading platforms include today FXall, FXconnect, Atriax, Hotspotfx, LavaFX and others. All of them are easily available on the Internet for your further research.

These hubs provide a crucial step for the non-banking participants (broker-dealers, corporations and fund managers, for example) allowing them to by-pass bank market makers in the first instance, and reducing costs substantially offering direct access to the market.

These professional platforms were followed by the first web based dealing platforms for the retail sector. Today there are hundreds of online Forex brokers whose business is focused on providing services to the small trader or investor, a phenomenon that mirrors what is already happening at the interbank level.

Online Retail Broker-Dealers

In the previous sections you have come to understand how the Forex market works. Now let's see how its inner workings can affect your trading by learning more about retail Forex brokers.

If you want to exchange one currency for another and make some profit, just like most individuals, you are unable to access the pricing available on the interbank market. You can't just barge into Citigroup or Deutsche Bank and start throwing Euros and Yen around, unless you are a multinational or hedge fund with millions of Dollars. To participate in the Forex, you need a retail broker, where you can trade with much inferior amounts.

Brokers are typically very large companies with huge trading turn over, which provide the infrastructure to individual investors to trade in the interbank market. Most of them are market makers for the retail trader, and in order to provide competitive two way prices, they have to adapt to the technological changes afoot in the industry, as we have seen above.

What does it mean to directly trade with a market maker? Every market maker has a dealing desk, which is the traditional method that most banks and financial institutions use.

The market maker interacts with other market maker banks to manage their position exposure and risk. Every market maker offers a slightly different price in a particular currency pair based on their order book and pricing feeds.

As trader, you should be able to produce gains independently if you are using a market maker or a more direct access through an ECN. But nevertheless, it's always essential to know what happens on the other side of your trades. To gain that insight, you first need to understand the intermediary function of a broker-dealer.

The interbank market is where Forex broker-dealers offset their positions, but not exactly the way banks do. Forex brokers don't have access to trading in the interbank through trading platforms like EBS or Reuters Dealing, but they can use their data feed to support their pricing engines. Enhanced price integrity is a major factor traders consider when dealing in off-exchange products, since most prices originate in decentralized interbank networks.

In order to quote prices to their costumers and offset their positions in the interbank market, brokers require a certain level of capitalization, business agreements and direct electronic contact with one or several market maker banks.

You know from chapter A01 that the Forex spot market works over-the-counter, which means there are no guarantors or exchanges involved. Banks wanting to participate as primary market makers require credit relationships with other banks, based on their capitalization and creditworthiness.

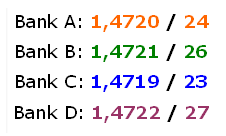

The more credit relationships they can have, the better pricing they will get. The same is true for retail Forex brokers: depending on the size of the retail broker in terms of capital available, the more favorable pricing and effectiveness it can provide to its clients. Usually this is so because brokers are able to aggregate several price feeds and always quote the tighter average spread to its retail customers.

This is a simplified example how a broker quotes a price for the GBP/USD:

The broker selects the higher ask price (Bank D) and the lower bid price (Bank C) and combines it to the best possible market rate at:

In reality, the broker adds its margin to the best market quote in order to make a profit. The price finally quoted to the costumers would be something like:

When you open a so called "margin account" with a broker-dealer, you are entering into a similar credit agreement, where you became a creditor towards your broker and he, in turn, a borrower from you.

What do you think happens the moment you open a position? Does the broker route the amount to the interbank market? Yes, he may do it. But he can also decide to match it with another order for the same amount from another of his clients, since passing the order through the interbank means paying a commission or spread.

By doing so, the broker acts as a market maker. Through complex matching systems, the broker is able to compensate orders of all sizes from all its costumers between each other. But since the order flow is not a zero equation - there may be more buyers than sellers at a certain time - the broker has to offset this imbalance in his order book taking a position in the interbank market. Obviously, many of these brokering functions have been significantly computerized, cutting out the need for human intervention.

The broker may also assume the risk, taking the other side of this imbalance, but it's less probable that he assumes the entire risk. On one hand, the statistics showing the majority of retail Forex traders loosing their accounts, may contribute to the appeal of such a business practice. But on the other hand, the spread is where the real secure and low risk business lies.

Richard Olsen explains the market maker's business model better than anyone:

But this is a fast, over-the-counter market; buyers and sellers don’t come in regular, offsetting waves, and when they do come, they all have to deal through the market maker. Whose primary objective is to limit risk (his own) and cover costs (his own). He needs to clear his books as quickly as possible; to reduce his risk he will lay off trades within five seconds, 10 seconds, or 10 minutes.

And to offload his inventory he will move the price to attract buyers and sellers.

The information is in the price, but what is it telling us?

Is Forex a zero-sum game? Ed Ponsi's answer to this controversial question throws some light into a subject which is often misunderstood:

There is a misconception among some traders that every trade must have a winner and a loser. [...] suppose you enter a long position on EUR/USD and at the same time, another trader takes a short position in the same currency pair. The broker simply matches the orders and collects the spread. This is exactly what the broker wants, to keep the entire spread and maintain a flat position.

Does this mean that in the above scenario one party has to win, and one must lose? Not at all, in fact both traders can win or lose; perhaps one has entered a short-term trade and the other has entered a long-term trade. Perhaps the first trader will take a profit quickly, but there is no rule that states the second trader must close his trade at the same time. Later in the day, the price reverses, and the second trader takes his profit as well. In this scenario, the broker made money (on the spread) and both traders did, too. This destroys the oft-repeated fallacy that every Forex trade is a zero-sum game.

From the previous chapter, you already know that Forex trading bears its transactions costs (more details on trading costs in the next Chapter A03) . Alone these costs prevent the order flow from being an absolute zero equation because entering and exiting the market is not free: every time you trade you pay at least the spread. From this perspective, the order flow is a negative sum game.

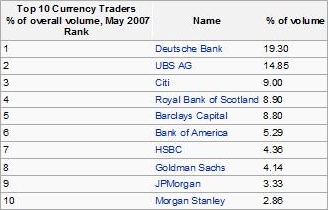

As you see from the order matching mechanisms brokers use, not all of the retail orders are dealt in the interbank market and are thus out of the official turnover estimations. Note as well that out of the entire volume transacted in currency exchange, only a part is considered spot Forex, around 1.9 billion Dollars according to the BIS 2007 survey.

In Forex there is another type of brokers labeled "non-dealing-desk" (NDD) brokers. They act as a conduit between customers and market makers/dealers. The broker routes the customer's order to another party to be executed by the dealing desk of the market maker. For this service brokers generally charge fees and/or are compensated by the market maker for the transactions that they route to their dealing desk.

As you see, either trading with a market maker or with a NDD broker, your order always ends up in a dealing desk.

In comparison with the mentioned brokerage models, the ECN brokers provide collected exchange rates from several interbank and non-interbank participants buying and selling through the platform. With such a platform, all participants are in fact market makers.

Besides trading directly, anonymously and without human intervention, each participant sends a price to the ECN as well as a particular amount of volume, and then the ECN distributes that price to the other participants.

The ECN is not responsible for execution, only the transmission of the order to the dealing desk from which the price was taken. In this system, spreads are determined by the difference between the best bid and the best offer at a particular point in time on the ECN. In this model, the ECN is compensated by fees charged to the customer and eventually a rebate from the dealing desk based on the amount of volume or order flow that it is given from the ECN.

It is important to point out that an ECN usually shows the volume available for trading each bid and offer, so the trader knows what maximum trade can be placed. ECN volume is only a reflection of what is available on any one ECN, not in the overall market. The market maker's responsibility is to provide liquidity under all conditions to its customers.

For success as a trader, it's not determining whether you trade through a market maker, non-dealing-desk or ECN broker. However, retail brokerage demands a due diligence, particularly in terms of regulation, execution speed, tools, costs and services. So you would do well to investigate thoroughly any broker you're planning to use.

Check the Brokers/FDMs news section to stay informed about the latest releases in the Forex Industry- everything about platforms, regulations, awards and much more.