2. Revenue Statistics

This section focuses on the overall performance of the trading system in terms of gains and losses of capital and help to fine-tune the evaluation process. The figures herewith disclosed should however not be used separately to determine the true worth of a system.

Return Rate

When evaluating a trading system or method, a statistical figure everyone probably first looks at is the Return Rate since that's ultimately what it is all about: accumulating profits. But only the most naive would base his/her valuation of a performance solely on a percentage return.

Why? Because returns, by themselves, include no information about the risk involved to get that return. The key point is that returns matter, but the path used to get those returns is also important.

This figure, also called Return On Starting Equity, is expressed in percentage terms and shows the profit or loss in relation to the start capital.

Maximum Run-up

This is defined as the system’s largest improvement in the trading equity curve between an equity low and a subsequent equity high. Basically it’s the far more pleasant opposite of a Maximum Drawdown, which is a pain for every trader. Periods of Run-up define the optimal trading conditions for the trading strategy as well. In other words, the type of market conditions that prevailed during the biggest winning Run-up are the conditions that are optimal for trading that particular strategy or system.

A trend following system, for example, should show its Maximum Run-ups during market trending phases, otherwise it may be not well designed and changes to its rules and parameterns may be necessary.

Drawdown

Also called Peak to Valley Drawdown, this is probably the second most mentioned statistical data after the Win rate. The Drawdown is the amount of money you lose trading, expressed as a percentage of your total trading equity. If all your trades were profitable, you would never experience a Drawdown but since every trading method incurs losses in order to achieve a profit, the Drawdown measures the money lost while achieving that performance.

Its calculation begins with a losing trade and continues as long as the equity curve hits new lows.

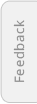

The example below shows the Drawdown as being the distance from the lowest point between two consecutive equity highs to the first of these highs.

For example, if you start an account with 10,000 Dollars and after a few trades you are down 2,000 Dollars. On the remaining 8,000 you are able to add 1,000 in profits but afterwards you lose again 2,000. This is a Drawdown of 30%, that is, a 30% loss on the original equity stake of 10,000 Dollars (8,000 + 1,000 - 2,000 = 7,000 = -30% loss of 10.000).

Now let's suppose that your account increases from the remaining 7,000 to 12,000 Dollars, achieving your first equity high, but then it drops to 6,000. Even if you are able to handle it again to a new equity high of 15,000, the lowest point between the two equity highs registers a new Drawdown of 50% (6,000 / 12,000).

The Drawdown can be also expressed as an Absolute Dollar Drawdown which is the same figure expressed in dollars.

Maximum Drawdown

This is the largest percentage drop in your account between two equity peaks. It can also be seen as the amount of capital needed to get your account back to breakeven after a string of losses.

If your account reached the lowest amount of 6,000 Dollars after having been at a high of 12,000, then you had a 50% Drawdown. If other Drawdowns were smaller than this, it remains as the Maximum Drawdown until the current performance surpasses that value.

Following the above example, if you were able to double your account to 20,000 and then double it again, no matter how much you are up on your account, the Maximum Drawdown would always be 100%. If you reach a 100% Drawdown, it means your account balance is zero.

The difficulty of recovering from Drawdowns is a topic covered in the last section of this chapter.

The Maximum Drawdown can also be called the Maximum Absolute Dollar Drawdown when expressed not in percentage terms, but in dollar amounts.

Average Dollar Drawdown

As the name suggests, it's a calculated average value of all the Drawdowns in a performance report. This is a useful number which helps traders decide on the trade size and risk control.

Average Dollar Drawdown = ( DD1 + DD2 + DDn ) / # of DDs

Maximum Closed Equity Drawdown

This statistic is a calculated Maximum Drawdown using closed trades only. Notice that the majority of performance reports don't make the distinction between closed and open equity Drawdowns. It's frequent to see a figure being reported as a Maximum Equity Drawdown but in reality the included data are only closed trades. This means that if there are any open trades in negative territory at the moment of the report, the data is not reflected in the overall performance.

Average Closed Equity Drawdown

Basically it's the same formula as with the Average Dollar Drawdown, but taking only closed trades. For example: in one week there is an equity peak in closed trades, in the following week the equity curve shows a 2% retracement, and a new peak is hit during the third week, then the 2% Drawdown is stored and averaged with all the other Closed Equity Drawdowns.

Gross Profit and Gross Loss

Sometimes called Total Gain and Total Loss, these are considered raw figures to be used in the calculation of more sophisticated ones. They refer to the total amount of money gained and lost during a certain period of time. Thus, the Gross Profit is obtained by summing up all the winning trades, and the Gross Loss is obtained by summing up all the losing trades.

Total Net Profit

The Total Net Profit is one of the first figures we want to look at when evaluating a trading performance and it's also one of the most widely quoted performance statistics. Simply put, it refers to how much capital has been earned during a certain period of time and it's calculated by subtracting Gross Loss from Gross Profit.

Don't worry too much about profits if you are in the development phase of your system. Although you want it to generate profits, your goal should not be only set at achieving a certain amount of money. Instead, concentrate on getting steady and well distributed gains with reduced Drawdowns.

Total Net Profit = Gross Profit – Gross Loss

Average Profit

The next figure you want to look at is the Average Profit per trade, also called Average Winning Trade. This figure indicates the average amount of money made in all winning trades during a certain period of time. You get this number by dividing the Gross Profit by the total number of winning trades.

It's obvious this number has to be positive - but make sure it is greater than your trading costs associated with slippage, spreads and/or commissions, to make the system profitable. The formula is:

Average Profit = Gross Profit / number of Win Trades

This figure, like many others, has to be seen in the context of other statistical data. For instance, if your performance shows that your Win Rate is below 50%, then the Average Profit should be bigger than the Average Loss Trade, in order to accumulate profits. If you can't keep the first figure larger than the second, then you won't make money even if you have a 50% Win Rate.

Average Loss

This is the same calculation as the above figure, but taking only losing trades into account. It is calculated by dividing the Gross Loss by the number of losing trades for a certain period of time as stated in the formula:

Average Loss = Gross Loss / number of Loss Trades

Profit Factor

This figure is calculated by dividing the Gross Profit by the Gross Loss. The resulting number will tell you how many dollars you’re likely to win for every dollar you lose. If the performance has been profitable, it means the Gross Profit was greater than the Gross Loss and the corresponding Profit factor has a value greater than one. In turn, unprofitable strategies and methods will produce Profit Factors of less than one. For example, a value of 2 would indicate that twice as much money was made from winning trades than was lost from losing trades. This also means the trader is selecting only those trades which have a good Risk to Reward Ratio.

Profit Factor = Gross Profit / the Gross Loss

Typically a good performance record should have a Profit Factor of 1.5 or more. However, a very high number is alarming: the sample data might not be big enough or the system might be over-optimized, which means its parameters are excessively adjusted to a certain market behavior.

This figure is also sometimes referred to as Profit-to-Loss Ratio.

Payoff Ratio

This is a ratio used by many traders to compare the expected return to the amount of capital at risk undertaken to capture these returns. The first number in the ratio is the amount of risk in the trade, and the second one is the potential reward of the trade.

It refers to the ratio of the Average Profit to the Average Loss per trade. For example, if you have risked 400 US Dollars per trade on average and your Average Profit is 1000 US Dollars, then your Payoff Ratio would be 1 to 2.5 (400 / 1,000). Trading is all about risk and reward, and you want to make sure you get a decent reward for your risk. It is not attractive to trade a system with a Payoff ratio near 1 unless it has a Win Rate greater than 50%.

Payoff Ratio = Average Profit per trade / Average Loss per trade

This is a different statistic than the previous Profit Factor since it does not weight gross income numbers but averages.

Expected Payoff

This ratio shows the expected gain (or loss) for each trade in absolute value. While the previous figure represents the Average Profit/Loss factor for each trade, this statistic is considered the expected profitability/unprofitability of the next trade. For example: you made 100 trades in one month and made a Total Net Profit of 1800 US Dollars. That means your Expected Payoff is 18 US Dollars (1800/100) per trade.

Expected Payoff = Total Net Profit / Total Number of Trades

When the total number of trades is multiplied by the Expected Payoff, the result should be the Total Net Profit.