- The historical background which gave birth to the Forex market.

- Floating exchange rates are not the only possible monetary system.

- The global market structure and the main financial centers.

- Other instruments besides the spot Forex.

- Advantages and disadvantages of the Forex market.

You don't have to be a trader to participate in the foreign exchange market: every time you travel and need to exchange your currency into a foreign currency, you are participating in it.

It also happens when companies from different countries buy and sell goods and services across national borders which require payments in non-domestic currencies. Either way, importing or exporting, there is going to be a transaction which takes one currency being swapped for another.

Nevertheless, in order to trade actively in this market, you should know how it came to be. The current market's shape and conditions are relatively new in the large history of money and that is what you are going to learn in this first chapter.

Despite your curiosity to jump directly into the more practical knowledge, you should know that an understanding of the historical circumstances from which this market emerged will gear you up with more insight when it comes to plan your future business in FX trading.

What about a little historical background about the largest financial market in the world?

1. The Origins

The FOREX (FOReign EXchange) Market is a cash-bank market established in 1971 when the US went off the gold standard adopted in the 1930's. At that time the US had to drop the gold standard after the 1929 crash and the British Pound became the currency of choice and the world's currency.

There have been other times before in Western History when paper money could be exchanged for gold. Throughout most of the 19th century and up to the outbreak of WW1, the world was on so-called "Classical Gold Standard" with all major countries participating in it. A gold standard meant that the value of a local currency was fixed at a set exchange rate to gold ounces. This allowed unrestricted capital mobility as well as global stability in currencies and trade

The participating countries were required to observe some rules: for example, it was particularly important that no country would impose restrictions on the importation or exportation of gold as a commodity nor a payment method. This was a guarantee for a free capital mobility based on supply and demand conditions.

Under this model, in which most central banks backed their paper money with gold, the currencies were supposed to enter in a new phase of stability, without the danger of an arbitrary manipulation of its value to increase inflation.

The Inter- and Afterwar Periods

During the interwar period the world powers tried to return to the gold standard at the exchange rates previous to 1914, which seemed to offer prosperity and stability, but the attempt did not succeed and exchange rates ended mostly floating. The classical gold standard was shattered by the outbreak end of WWI and collapsed under its violence. Private trade and financial transactions were suspended, gold exports were banned, and each country started to print money to finance the war effort. The 1920s-30s were characterized by recessions and the Great Depression. There was a hegemonic power shift from the UK to the US.

In the aftermath of World War II, the system became a US-centered fixed rates under a new international gold standard and the world economy experienced high growth, price stability and movement toward freer trade. Unlike the classical gold standard days, however, there were severe restrictions on private capital mobility.

The gold standard had its inefficiencies the way it was handled: the combination of a greater supply of paper money without the gold to back it led to devastating inflation and resulted in political instability.

The problem with gold is that its quantity is too constraining: the world supply of gold was insufficient to make the Bretton Woods system workable -particularly as the use of the Dollar as a reserve currency was essential to create the required international liquidity to sustain world trade and growth. As economies grew stronger and needed more money to pay imported goods, there was no sufficient gold reserves to pay for it. As a result the monetary mass decreased, the interest rates increased and the economic activity slowed down and the economy entered in a recession.

In such cases, the low prices of U.S. manufactured goods were then attractive for other nations. These started to import massively and by doing so they contributed to the increase of the monetary mass in the exporting country. This, in turn, allowed to ease the interest rates and subsequently the economy to grow. It was evident that the mechanism linking inflation/deflation with gold flows was not able to adjust macroeconomic imbalances. It was thought that under a gold standard, a country with a current account deficit would imply an outflow of gold. The loss of gold means less money supply, so the country would experience a price deflation. This would make its goods become cheaper in the global markets, making imports rise and exports fall, improving the current account again.

These peak-bottom periods alternated until the WWI interrupted the commercial flow and the gold exchange. Until WWII, currency speculation was almost inexistent and even not very much favored by institutions. The Great Depression and the abolition of the gold standard in 1931 led to a pause in the exchange activity. But later, after the transition period of 1971-73, the market suffered a series of changes which shaped the actual global monetary system: the major currencies started to float.

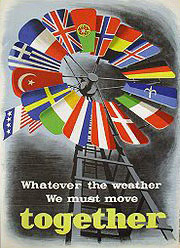

The Bretton Woods Regime, the Transition Era

After WW II the world needed a stable currency and a monetary agreement was reached by July 1944: seven hundred and thirty delegates from forty-four allied nations came together in Bretton Woods, NH, US The reason for the gathering was the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference. For the first time in history monetary relations amongst the world's major industrial states were governed; it was the first time a system was implemented, in which the rules for commercial and financial relations were negotiated and agreed upon. The dollar's role was formalized under the Bretton Woods monetary agreement and other nations set official exchange rates against the Dollar, while the US agreed to exchange Dollars for gold at a fixed price on demand by central banks.

It is said that many political reasons ended up resulting in the Bretton Woods agreement. Just to name a few: the two world wars and the interwar years, which was followed by the need to rebuild international economy; the Great Depression; the strong and shared belief in capitalism; USA.'s status of dominant power; the need for an economic system that would act as security.

This system functioned well for a brief period. However by about 1958 the initial worldwide Dollar shortage had turned into an overabundance.

Pegged, Semi-Pegged and Floating Condition

Considering the outcome of floating rates in the 1930's, which had negative worldwide consequences, the participants of the conference were eager to adopt basic rules with which to regulate the international monetary system as well as to create a policy in which the exchange rate of each currency would have a fixed value.

And indeed such measures were implemented: new international institutions were established to promote foreign trade and to maintain the monetary stability of the global economy.

The Bretton Woods system was an effective system that controlled conflict for many years. It could achieve the common goals that were set, however, its lifespan was finally short as it collapsed by 1971.

It was also agreed that currencies would once again be fixed, or pegged, but this time to the US Dollar, which in turn was pegged to gold at 35 USD per fine ounces of gold. This meant that the value of a currency was directly linked to the value of the US Dollar. At that time if you needed to buy British Pounds, the value of the Pound would be expressed in US Dollars, whose value in turn was determined by the value of gold. If a country needed to readjust the value of its currency, it could approach the IMF to change the pegged value of its currency.

The peg was maintained until 1971 when the US Dollar could no longer hold the value of the pegged rate. From then on major governments adopted a floating system and all attempts from major economies to move back to a peg were eventually abandoned.

The Bretton Woods agreement was also meant to accomplish several other purposes: to avoid the capital evasion between nations, to restrict speculation with currencies, and to prevent each country from pursuing selfish policies, such as competitive devaluation, protectionism and forming trade blocks More generally speaking, to create a new world economic order. In fact, this new model brought two main advantages to the US: in on hand the revenues from the money creation itself called seigniorage and on the other hand the possibility to hold a trade deficit for a very long time.

John Maynard Keynes, chairman of the Bank Commission at the Bretton Woods conference, and one of its intellectual founding fathers, envisaged an international monetary clearing union that in reality would have been a world central bank creating and using a world currency he called 'bancor'.

The problem, as Keynes well understood, was that an international trade and payments system - that relied on flexible exchange rates system with multiple currencies - would be inherently unstable. Keynes' proposal for a clearing union would penalize both deficit and surplus countries. Each country would have an official account in this mechanism, and all balance of payments surpluses and deficits would be recorded and settled through these accounts. There would be an incentive for both types of economies to run balanced trading systems as each country would bear the responsibility for correcting its imbalance.

This truly visionary proposal to create a mighty settlement union for all countries was seen as negative from US point of view.

Keynes' plan was not fully adopted but, in recognition of the pragmatic validity of his proposed solution, the exchange rates were fixed relative to the US Dollar and the Dollar backed by gold reserves. All other currencies could not deviate more than 10% to both sides of the fixed rate.

The US proposal, which was finally adopted, meant that each country would contribute to a common fund and member countries with surplus or deficit imbalances would have to purchase hard currencies from this fund. At the time, the UK was a deficit country and the US a surplus country, and only deficit countries would bear the responsibility for correcting the imbalance.

In case of such a fundamental imbalance, the central bank responsible of the currency had to ask authorization to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to bring the value of its currency back to accepted levels. The IMF and what has evolved to be today the World Bank, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, emerged at that time to administer the new system.

At this point let's summarize the main features of the Bretton Woods system:

- It's a Dollar-based world payments arrangement: officially, the Bretton Woods system was a gold-based system which worked symmetrically for all countries. But in reality, it was a US-dominated system, which means the US provided domestic price stability (or instability) that other countries could (or should) "import". As the US did not itself engage in exchange rates intervention, which would have been desirable, all other countries had the obligation to intervene themselves in the currency market to fix their exchange rates against the US Dollar.

- It was a semi-pegged exchange rate system: this means that exchange rates were normally fixed but permitted to be infrequently adjusted under certain conditions. Members were obligated to declare a par value (a 'peg') for their national currency and to intervene in currency markets to limit exchange rate fluctuations within maximum 'band' of one per cent above or below parity. At the same time, members also retained the right, whenever necessary and in accordance with agreed procedures, to alter their peg to correct a 'fundamental disequilibrium' in their balance of payments. This arrangement was thought to combine exchange rate stability and flexibility, while avoiding mutually destructive devaluation.

- Tight capital mobility: by contrast to the classical gold standard of 1879-1914, when there was free capital mobility, member countries could impose capital-account regulations and severe exchange controls.

- Macroeconomic growth reached historically unprecedented highs: this was achieved through global price stability and trade liberalization from the mid 1950s to the late 1960s.

The Dollar Shortage

Later, during the 50's, the Bretton Woods system was under enormous pressure and needed help to function properly when the major economies started to evolve in different directions. While the classical gold standard collapsed because of external forces (the outbreak of WWI), the Bretton Woods regime failed due to internal inconsistency. US monetary policy was the system's anchor and the growing inflation in the US destabilized the system until it started to disintegrate.

The expansion of international trade and the massive capital movements led to a Dollar shortage.

After WW II, Europe and Japan needed to import from US all kinds of manufactured goods and machinery for its own reconstruction while US wanted to favor Western European countries in front of the menace of Eastern European countries and the USSR. But there were not enough Dollars in circulation. So in 1948 the US decided to give west Europe an economic aid, under the name of the Marshal Plan, officially called the European Recovery Program.

In the 60's the situation started to revert and an oversupply of Dollars in circulation gradually appears. The Vietnam war, welfare expenditure and the space race with the USSR were the major reasons for the increased US government spending. When US inflation began to accelerate, other countries refused to import it into their economies. This whole situation destabilized the exchange rates agreed upon in Bretton Woods.

Shortage in international currencies and abundance of US Dollars rise some doubts about its convertibility to gold. The already high trade deficit of the US led to speculative pressures awaiting a strong devaluation of the US Dollar versus gold. A series of readjustments held the system for a while but finally, on August 15, 1971, everything changed. US President Nixon suspended the gold convertibility standard and in 1973 the US formally announced the permanent floating of the US Dollar, thereby officially ending the fixed exchange rate regime and the Bretton Woods system.

With the too rapid growth of dollar credits around the world, gold backing of the dollar proved unsustainable. The Bretton Woods agreement collapsed in 1973, but it enthroned the dollar as the international medium of exchange. This unique role of the dollar continues to the present day.

US-Dollar-Based World Payments Arrangement

The rapid growth of the industrialized economies after WW II created a growing demand for dollar balances around the world. The more of its own currency a central bank issued, the more Dollars it wanted as underpinning for its currency.

During the Bretton Woods period, the US ran large current account surpluses which would have drained Dollars from abroad. But capital outflows in the form of grants and direct investments by the US were greater than its current surpluses. This means the US was lending more than it was borrowing, thereby satisfying the world’s growing demand for Dollar liquidity, even while it remained a net creditor. The result was an accumulation of Dollar assets by foreign firms and central banks.

With a US-Dollar-based world payments arrangement, the US can conduct its monetary policy independent of exchange rate fluctuations. In this respect, other countries operate at a disadvantage and have to subordinate their domestic monetary policies in order to stabilize their currencies against the dollar: domestic inflationary threats emerge if their currencies depreciate against the Dollar and a loss of competitiveness in world markets emerges if they allow a substantial appreciation of their currency against the Dollar. Whithin this monetary framework the US can issue Dollar-denominated claims to the rest of the world which may never have to be redeemed so long the domestic purchasing power of the Dollar is mantained. This unique advantage the US has to borrowing in its own currency, for other countries is seen as a great convenience to have the US Dollar as a safe reserve asset. Only a serious loss of confidence in the Dollar could depose it as the primary medium of international exchange.

Different Regimes

For instance, if you are a European wanting to travel to the US and the exchange rate for EUR 1.00 is USD 1.50 this means that for every Euro, you can buy one and a half US Dollar.

There are different ways the price of a currency can be determined against another:

Through a fixed, or pegged, rate which is a rate the central bank sets and maintains as the official exchange rate. In this case a set price will be determined against a major world currency (usually the US Dollar, but also other major currencies such as the Euro, the Yen, or a basket of currencies). In order to maintain the local exchange rate, the central bank buys and sells its own currency on the foreign exchange market in return of the currency to which it is pegged. To do this, the central bank must keep enough foreign reserves to release or absorb into or out of the market.

Some governments may also choose to have a semi-peg whereby the government periodically reassesses the value of the peg and then changes the peg rate accordingly. Usually the change is devaluation but one that is controlled so that market panic is avoided. This method is often used in the transition from a peg to a floating regime.

Although the peg has worked in creating global trade and monetary stability, it was only used at a time when all the major economies were a part of it.

And while a floating regime has its flaws, it has proven to be an efficient means of determining the long term value of a currency and creating equilibrium in the international market.

You may now ask: "Why the need to fix a currency?" It has to do with the aim to create a stable atmosphere for foreign investment, specially among developing nations. If the currency is pegged, the investor will always know what its value is and will not fear hyperinflation. However the peril exists that such countries experience financial crisis as well, like Mexico in 1995 and Russia in 1997.

An attempt to maintain a high value of the local currency to the peg can result in the currencies eventually becoming overvalued. This means that the governments could no longer meet the demands to convert the local currency into the foreign currency at the pegged rate. With speculation and panic, investors would start to convert their currency into foreign currency before the local currency is devalued against the peg, depleting the central bank's foreign reserves.

There is also a floating condition, which allows the Forex market to function as we know it nowadays with most of the major currencies. A floating exchange rate is determined by the private market through supply and demand. A floating rate is often termed "self-correcting", as any differences in supply and demand will automatically be corrected in the market.

A floating exchange rate is constantly changing as a decrease in demand for a currency will lower its value in the market. This in turn will make imported goods more expensive and stimulate demand for local goods and services. As a consequence, more jobs are created, and hence an auto-correction occurs in the market.

In a floating regime, the central bank may also intervene when it is necessary to ensure stability and to avoid inflation; however, compared with a fixed system, it is less frequent that the central bank of a floating regime interferes.

A country can also opt to implement a dual or multiple foreign exchange rate system, where both modalities run in parallel. Unlike a pegged or floating system, the dual and multiple systems consist of different rates, fixed and floating, running at the same time. The fixed rate is usually a preferential rate and the floating a more discouraging one.

While the fixed rate is only applied to certain segments of the market, like the import/export of essential goods, the floating rate is set by the forces of supply and demand in the market and is applied to non-essential goods like luxury imports.

This system is also usual in transitional periods as a means by which governments can quickly implement control over foreign currency transactions. In those cases, instead of depleting its foreign reserves, the government diverts the heavy demand for foreign currency to the free-floating exchange rate market.

As with the other solutions, a multiple exchange rates system is not free from negative consequences: creating artificial conditions for certain market segments is one of them. But it could also be used as an effective means to address the problem in the balance of payments developed under the conditions of a completely free floating system.

Note that none of these systems are perfect, but that all are thought as mechanisms to deal with those underlying problems in economic crisis and inflation periods. Their aim is to eventually keep the equilibrium in the monetary system.

These are the four mentioned exchange rate systems, or regimes:

- Pegged exchange rate system: the value of the currency is tied to another currency, to a basket of currencies or to the price of gold. The purpose of a fixed exchange rate system is to maintain a country's currency value within a very narrow band.

- Semi-pegged exchange rate system: the central bank periodically readjusts the fixed (pegged) value of its currency.

- Floating exchange rate system: the value of a currency changes freely and is determined by supply and demand in the Forex market.

- Multiple exchange rate system: both systems are simultaneously used in different segments of the economy.